How has COVID-19 changed our public spaces?

Photo by Christopher Michel

Photo by Christopher Michel

This is a continuation of our series, COVID-19 and the urban environment.

From the first emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China to its worldwide spread, the disease has commonly been understood as an urban phenomenon. Urban areas have been hit the hardest, and even those with lesser outbreaks have already seen significant changes to work and social life, and to their urban landscapes and built forms. Over the next several weeks, we will be releasing findings from research we conducted this past summer on COVID and urban life. We aim to provide a broad look at current responses, tactics, and consequences of the pandemic.

Public spaces

There has been much debate about the definitions of public space and whether it can be publicly or privately owned, inside or outside, restricted or free, and democratic or otherwise (Gehl & Matan, 2009). For example, UNESCO (n.d.), defines public space as “an area or place that is open and accessible to all people, regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, age or socio-economic level”. Such spaces include plazas, squares, parks, sidewalks, streets and even virtual spaces made available through the internet (UNESCO, n.d.) while Miller (2007) defines public space as “a kind of hybrid of physical spaces and public spheres’ and bases her definition ‘on the assumption that physical space is important to democratic public life”. From these definitions, one can decode public spaces as being a combination of open green spaces and the built environment. Regardless, restrictions on the use of these public spaces along with confinement and social distancing were initially thought to be key in reducing the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and protecting public health (Honey-Roses et al, 2020).

A global survey was done by Gehl, an urban design consulting firm based in Copenhagen, Denmark, on public space usage amid COVID-19 (O’Connor, 2020). According to O’Connor (2020), the survey consisted of 2,000 respondents from around the globe who shared what roles public spaces played in their everyday lives during this time. The survey revealed that over a third of the respondents stated that they did not use public spaces at all, preferring to stay at home with the occasional run of essential errands. The remainder of the respondents who used public spaces went to ones near to their homes, including neighbourhood streets, sidewalks, and local parks.

This increase in the usage of streets and sidewalks has become a widespread occurrence in several cities around the world as public transit ridership dropped by more than 80% since January of 2020 (Bliss, 2020).

This comes from cities allowing for individuals to leave their homes for brief periods of time, whether for exercise or to get fresh air. As cities make alterations to their street space in an effort to combat COVID-19, the pandemic has revealed that cars have taken up so much space that there’s not much room left over for people (Roberts, 2020) since it is not always easy to maintain the recommended one to two metres apart directive for people who decide to go out (Aviles, 2020).

As summer came and went, alterations to the streetscape varied in different cities, with some (as in some parts of Montreal) closing the streets to cars and other vehicles while opening them up to people. In the US, cities either closed their streets completely, introduced fare suspension, provided free bike sharing and temporary bike lanes or have implemented automated crossing so that pedestrians don’t have to push buttons to cross streets (Bliss, 2020). In Bogota, the city turned over a 120km network of streets to bicycles and opened up an additional 117km of temporary space for bikes and pedestrians by taking away car lanes. This movement inspired other cities around the world to follow suit such as Berlin, Montreal, Portland, Vancouver and Paris (Roberts, 2020).

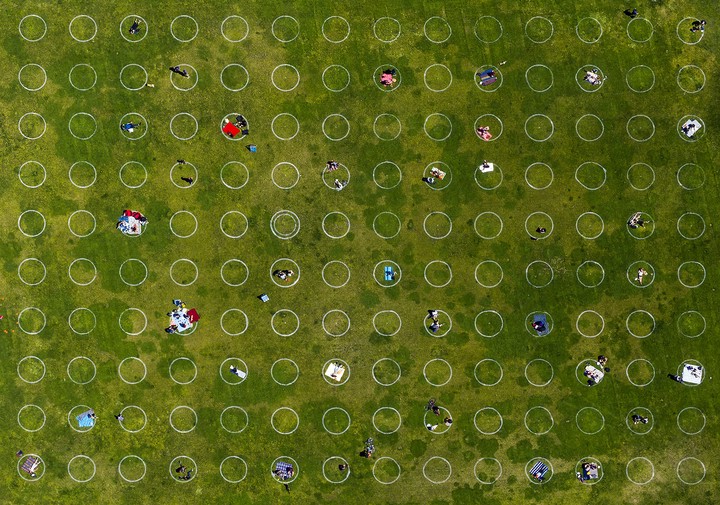

Open green spaces such as parks, beaches, nature trails, and golf courses for the most part remained open this year, while more enclosed, man-made places like public libraries, playground equipment, gyms, community centres and other cultural and recreational facilities, were found to pose a higher transmission risk and were more often closed.

Most proponents of keeping public spaces such as parks open argue for their health benefits. According to Tufecki (2020), green spaces are good for the immune system and mind and can be rationed to allow for social distancing. The author asserts that shutting down all parks and trails may have seemed like a good idea in the short term, when the healthcare system was overrun, but in the medium to long run, it would turn out to be a “mistake that backfires at every level”. Tufecki (2020) asserts that exercise, sunshine, fresh air and the outdoors are essential as a way to sustain population health and resilience. “A lack of vitamin D, which our bodies synthesize when our skin is exposed to the sun, has long been associated with increased susceptibility to respiratory diseases. The outdoors and sunshine are such strong factors in fighting viral infections” (Tufecki, 2020).

While parks are not cited as posing any specific dangers in and of themselves, they offer a space for groups to gather. The fear of overcrowding and the potential spread of COVID-19 drove the closure of many parks worldwide (Tufekci, 2020). Municipal and national parks have been closed in cities such as Zurich, London, and many others in the U.S., but many subsequently reopened as we came to understand that the risk of outdoor transmission is significantly lower than in indoor spaces, especially when additional social distancing measures are in place. In Montreal, officials have threatened to close parks if residents do not adhere to social distancing and safety guidelines (Magder, 2020).

REFERENCES

Aviles, G. (2020, April 23). An urban planner mapped every NYC street, showing it's 'extremely difficult' to maintain social distance. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/urban-planner-mapped-every-nyc-street-showing-it-s-extremely-n1189936

Bliss, L. (2020, April 22). Mapping How Cities Are Reclaiming Street Space. Retrieved from https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2020/04/coronavirus-city-street-public-transit-bike-lanes-covid-19/609190/

Gehl, J., & Matan, A. (2009). Two perspectives on public spaces. Building Research & Information, 37(1), 106–109. doi: 10.1080/09613210802519293

Honey-Roses, J., Anguelovski, I., Bohigas, J., Chireh, V., Daher, C., Konijnendijk, C., ... & Oscilowicz, E. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Public Space: A Review of the Emerging Questions.

Magder, J. (2020, April 2). Don’t gather in Montreal parks or we’ll close them, Valérie Plante warns. Retrieved from https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/dont-hang-out-in-parks-plante-warns-montrealers/

Miller, K. F. (2007). Designs on the Public: The Private Lives of New York’s Public Spaces. doi: 10.5749/j.ctttv5pq

O'Connor, E. (2020, May 11). Public Space plays vital role in pandemic. Retrieved from https://gehlpeople.com/blog/public-space-plays-vital-role-in-pandemic/

Roberts, D. (2020, April 13). How to make a city livable during lockdown. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/cities-and-urbanism/2020/4/13/21218759/coronavirus-cities-lockdown-covid-19-brent-toderian

Tufekci, Z. (2020, April 8). Keep the Parks Open. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/04/closing-parks-ineffective-pandemic-theater/609580/

UNESCO. (n.d.). Inclusion Through Access to Public Space: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/urban-development/migrants-inclusion-in-cities/good-practices/inclusion-through-access-to-public-space/