Abstract

This report presents the first comparative analysis of short-term rentals in major Canadian cities. It relies on the most comprehensive third-party dataset of Airbnb activity available, and new methodological techniques for spatial analysis of big data. Across the Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver regions, 81,000 Airbnb listings have been active at some point in the last year, and 51,000 in May 2017. Airbnb hosts in Canada’s largest three metropolitan regions earned a collective $430 million in revenue last year, an average of $5,300 per listing and a 55% increase over the year before. There are now 13,700 entire homes rented 60 days or more per year on Airbnb in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver, each of which is unlikely to be rented to long-term tenants. Cities should regulate short-term rentals according to three simple principles–1) one host, one rental; 2) no full-time, entire-home rentals; 3) platforms responsible for enforcement.

This report presents the first comparative analysis of short-term rentals in major Canadian cities. It relies on the most comprehensive third-party dataset of Airbnb activity available, and new methodological techniques for spatial analysis of big data.

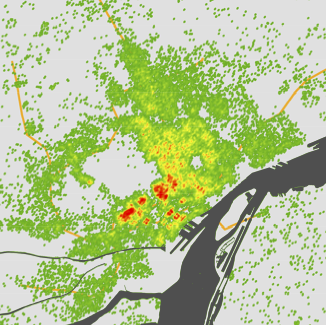

Across the Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver regions, 81,000 Airbnb listings have been active at some point in the last year, and 51,000 in May 2017. Montreal had the largest number for most of the year, but Toronto is now taking first place. These listings are heavily concentrated in the central cities of the three CMAs, and they are growing rapidly; the three cities have experienced a 50% year-over-year increase. A majority of listings in all three cities are entire homes rather than private rooms.

Airbnb hosts in Canada’s largest three metropolitan regions earned a collective $430 million in revenue last year, an average of $5,300 per listing and a 55% increase over the year before. This growth is driven by Toronto, where total revenue nearly doubled year-over-year, and where average revenue per listing is also growing strongly. Revenue is highly concentrated among the most successful hosts; 10% of hosts earn a large majority of overall revenue.

There are now 13,700 entire homes rented 60 days or more per year on Airbnb in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver, each of which is unlikely to be rented to long-term tenants. They account for one sixth of all Airbnb listings, and a majority of nights booked on the service. Even more worryingly, these listings are growing around 25% more rapidly than other categories of listings. Many neighbourhoods—above all in Montreal—have seen two or three percent of their entire housing stock converted to de facto hotels.

A third of all active Airbnb properties are “multi-listings”, whose hosts administer two or more entire homes or three or more private rooms. The most successful of these hosts earn millions of dollars per year running commercial short-term rental services across dozens or even hundreds of homes, most of which are no longer able to support a long-term resident. The “triple threat” is short-term rental listings which are full-time, entire homes, and multi-listings. Even though there are only 6,500 of these listings in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver—8% of the total active listings—they account for 34% of total revenue. These listings are growing more rapidly than any other category of listing, and in Toronto their share of total revenue increased by 125% in a single year.

Airbnb has removed as many as 13,700 units of housing from rental markets in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. In some areas this represents more than two percent of the total housing stock—a number comparable to the rental vacancy rate in the three cities. In general, these are neighbourhoods with above average rents, but there are significant economic pressures threatening further conversions of long-term rentals to de-facto Airbnb hotels in a number of more affordable areas—particularly those lying on mass transit lines. In the last year, conversions to short-term rentals have outpaced new home construction in a number of neighbourhoods.

Short-term rentals often operate in legal grey zones, able to avoid existing accommodation regulations and taxes, and are now increasingly being targeted with specific regulations. The Province of Quebec was the first major Canadian jurisdiction to legalize short-term rentals, implementing a regime focused on recovering tax revenues. Toronto and Vancouver, acknowledging the wide range of impacts from short-term rentals have both proposed more stringent regulations, including limiting short-term rentals to principal residences.

Cities should regulate short-term rentals according to three simple principles: 1) one host, one rental; 2) no full-time, entire-home rentals; 3) platforms responsible for enforcement. The City of Amsterdam provides an encouraging example of these principles in practice, while Fairbnb.ca’s recent regulatory proposals for Toronto offers a closer-to-home example.

The report is available to download here .